#22: Notes on travel retail: Trader Joe's

Trader Joe's is one of America's best retailers. What can the travel industry learn from them? And how might we apply "intensive buying," the TJ's secret sauce, to the travel world?

'“Retail” comes from a medieval French verb, retailer, which means “to cut into pieces.” “Tailor” comes from the same verb.

– Joe Coulombe, Becoming Trader Joe (95)

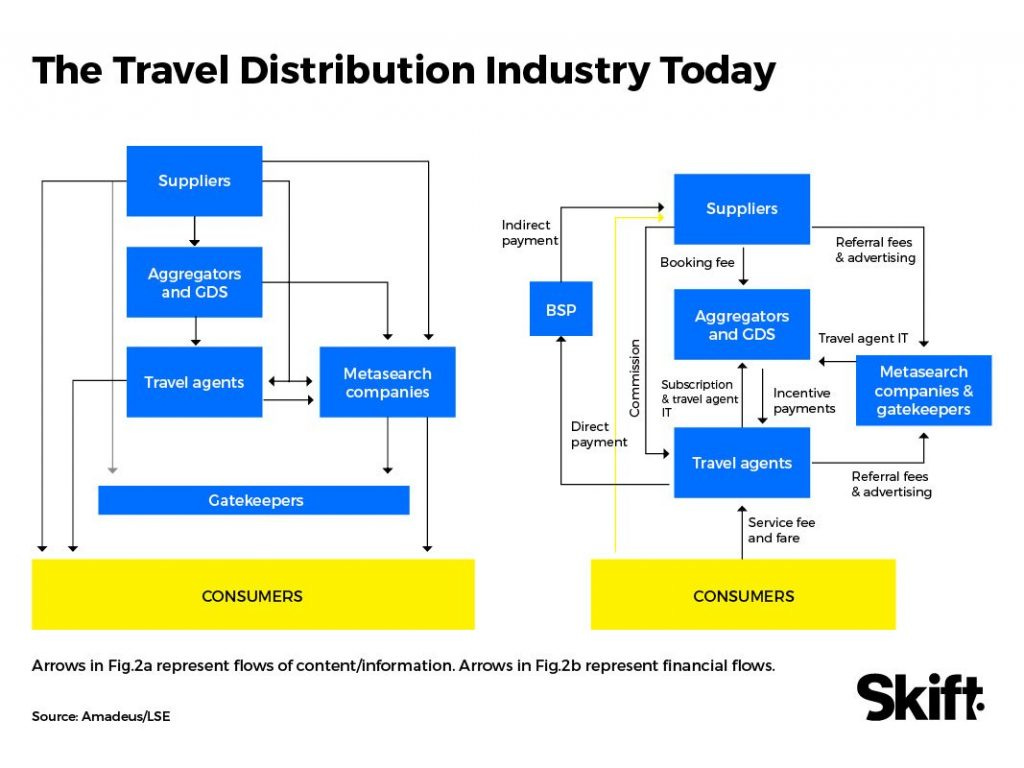

In the travel industry, the distribution battles never end. Airlines and hotels fight intermediaries for access to the customer - can they increase their direct business or will they continue to rely on corporate travel agencies and OTAs? The OTAs, like Expedia and Booking.com, are squeezed by reliance on advertising and by those airlines’ and hotels’ increasing ability to bypass them with easier booking, better customer service, and richer loyalty programs. Meanwhile, there’s buzz about AI somehow replacing or supplementing OTAs, though nobody really knows what that means. And of course, luxury travel advisors are thriving.

Rather than wade into all that complexity, I’m going to do something different. I’ve been curious to learn from the world’s great retailers outside travel. This will be the first of an occasional series on how the lessons of non-travel retailers could potentially be applied in the travel business.

I’ll start with Trader Joe’s, one of the most unconventional grocers in the US.

Becoming Trader Joe

Trader Joe’s is a specialty grocer with small stores, unique products, surprisingly low prices, relatively few choices, and the majority of products are unbranded or store-branded. The founder, Joe Coulombe, wrote Becoming Trader Joe about his time running the company from the founding in the 1960s through his departure in the 1980s.1

In this piece, I’ll pull out themes from Joe Coulombe’s memoir and reflect on how they might apply to travel retailing.

The role of the retailer

After a few store concepts that evolved over a decade, Coulombe settled on the ultimate formula for the Trader Joe’s we know today. Their “most important strategic decision,” he writes, “was to become a genuine retailer” (95). If you couldn’t tell from the fact I used this quote up top, this one blew my mind:

Retail’ comes from a medieval French verb, retailer, which means “to cut into pieces.” “Tailor” comes from the same verb. (95)

What did that actually mean for Trader Joe’s?

The fundamental job of a retailer is to buy goods whole, cut them into pieces, and sell the pieces to the ultimate consumers. This is the most important mental construct I can impart to those of you who want to enter retailing. Most “retailers” have no idea of the formal meaning of the word. Time and again I had to remind myself just what my role in society was supposed to be. […]

[Originally], we did everything we could to avoid retailing. We tried to shift the burden to suppliers, buying prepackaged goods, hopefully pre-price-marked (potato chips, bread, cupcakes, magazines, paperback books) so we had no role in the pricing decision. The goods were ordered, displayed, and returned by outsider salespeople. (95)

By this definition, are OTAs retailers? Not really, or at least not fully. They’re more like the supermarkets that Joe Colombe was counter positioning against. Expedia and Booking basically take the inventory that airlines and hotels give them and then make it searchable and bookable. Is that useful? Yes, of course. But it’s not really retailing. They’re not “cutting” anything. In fact, there’s nothing really differentiated about it at all.

OTAs were super useful in the 1990s, when all this information was locked in computer systems that the public couldn’t access or it was completely offline. These days, that information is basically a commodity (because of the success of these OTAs!). OTAs struggle to add value beyond search and comparison. And as many frequent travelers will tell you, it’s often better to book direct with the hotel or airline - if anything goes wrong, you can deal with the operator’s employees rather than having them tell you to call the travel agent.

So who are the genuine retailers in travel? One example are the European tour operators, like TUI. They buy blocks of rooms, negotiate steep discounts, and often package them with other components (like flights, transfers, and activities).

Could there be opportunities for other types of true retailers? I think so.

The overeducated and underpaid demographic

In the 1970s, Trader Joe’s became known for selling wine and European cheese at great prices. During that period, American supermarkets sold crappy branded beer and sliced bread. That choice to sell fancy products for cheap wasn’t a coincidence:

The keystone […] of Trader Joe’s was a small news item in Scientific American in 1965 […]. The news items said that, of all the people in the United States who were qualified to go to college in 1932, in the pit of the Depression, only 2 percent actually did. By contrast, in 1964, of all the people qualified to go to college, 60 percent in fact actually did. […]

A second news item, one from the Wall Street Journal, told me that the Boeing 747 would go into service in 1970, and that it would slash the cost of international travel. […]

We had noticed that people who traveled - even to San Francisco - were far more adventurous in what they were willing to put in their stomachs. Trade is, after all, a form of education. (26)

In the travel world, I suspect this overeducated and underpaid demographic continues to be underestimated.

To focus on the US, even more people have gone to college, even more people are interested in travel abroad, and even more people are “underpaid.”

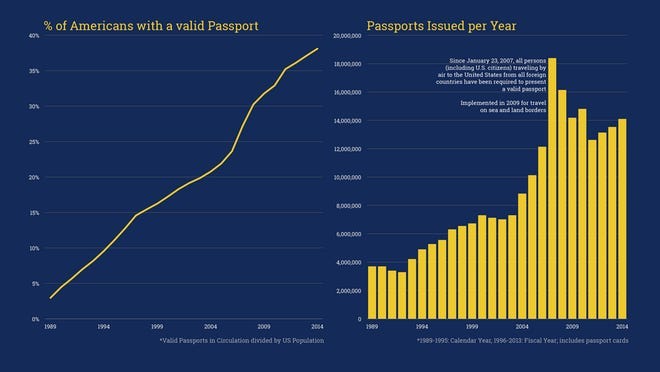

American culture has become more outwardly curious than it’s given credit for. Foreign television and movies are increasingly consumed en masse (think of Squid Games) and foreign foods are widely distributed. More than 50% of Americans now have passports, up from 5% in 1990.

Who’s selling travel at a great value (not necessarily the cheapest!) to the overeducated and underpaid demographic? In my opinion, not as many as could be.

If you browse Conde Naste or Travel + Leisure, you’d think the average vacation costs $1,000/person/day. For example, look at the list of 2024’s top tour operators. There’s lots of investment and innovation going into serving luxury travelers, and big press and marketing budgets to promote operators. I’m not criticizing any of that - I work for a high-end company myself.

Innovations in lower-cost travel have focused on self service, including democratizing information (infinite information on the internet), democratizing booking (through OTAs), and lowering airfares. That’s all great, but I suspect there’s room for innovative and affordable travel retailers in the US that serve customers with sophisticated taste and limited budgets.

Excel in value or uniqueness

This one’s simple and - as with many simple things - very difficult to do in practice:

“We would not carry any item unless we could be outstanding in terms of price (and make a profit at that price) or uniqueness” (97)

Many, many times in travel, neither of these are true. Products are not differentiated between retailers and they’re sold at the same prices on all platforms. Think of hotels on Expedia vs Booking. Think of activities on Viator or Get Your Guide. The biggest retailers in travel are supermarkets. They reliably have everything you need, but they engender no customer loyalty.

Again, I think tour operators do a better job here. You have to admit that Great Value Vacations are a great value and that Intrepid offers pretty adventurous trips.

Limited Assortment

When Coulombe settled on the final concept for Trader Joe’s, one of the components of the strategy was to “carry individual items as opposed to the whole line” (98).

We wouldn’t try to carry a whole line of spices, or bag candy, or vitamins. Each SKU (a single size of a single flavor of a single item) had to justify itself, as opposed to riding piggyback into the stores so we had a “complete” line (98)

That willingness to carry a limited assortment enabled the commitment (above) to be best in price or uniqueness. If they couldn’t do either, they’d just drop the product.

Coulombe reflected later:

Retailers seem to be falling into two distinct SKU modes: those with under 4,000-5,000 SKUs and those with over 25,000 SKUs. In the low-SKU class we find Costco. […]

The SKU dichotomy is echoed by another division among retailers: those who feel they must carry certain brand and types of products (most chains) and those who feel they don’t have to carry any particular brand or type of product (Costco, Stew Leonard’s, Trader Joe’s), unless it provides value for the customer, and is profitable for the retailer.” (170)2

In TJ’s case, the limited-selection was motivated by efficiency (making the best use of limited in-store space). Limited selection was enabled by intensive use of unbranded and store brand items (no need for competing branded versions of the same product) as well as the the cheap or unique approach explained above. You don’t need five version of a product - you only need the best value and perhaps a unique twist on that product.

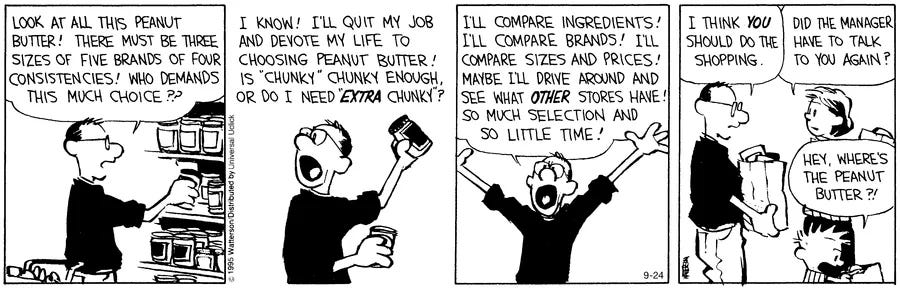

From a customer perspective, it may seem like TJ’s limited product assortment is a disadvantage, but it actually makes shopping more pleasant - it eliminates the tyranny of choice (read more from Srikant Chari).

One last point from Coulombe:

The greatest advantage of a limited-SKU retailer is that the employees at all levels can become truly knowledgeable about what they sell. (164)

This is an under-appreciated benefit in the travel world as well (and one I’ve written about before).

Most travel retailers follow the supermarket (or Amazon.com) approach with infinite choice. That works, of course, but I wonder if there’s opportunity for a counter-positioned retailer that takes full advantage of a limited product assortment.

Discontinuity

The willingness to do without any given product is one of the cornerstones of Trader Joe’s merchandising philosophy. (126)

If a product didn’t sell or it wasn’t available at a good price, they just wouldn’t carry it.

Discontinuity also allowed Coulombe to take advantage of opportunities that others wouldn’t. It all started with wine, which TJ’s sold early on and influenced how they sold other products. Coulombe writes:

The foremost character of wines […] is that each vintage, and each batch within a vintage, is separate, unique, discontinuous, discrete. […]

This philosophical approach put us in conflict with the mainstream of American retailing, which emphasizes continuous products. […]

Because of our wine background, we liked and embraced discontinuous lots of food. (132-134)

Here are two examples:

Vintage-dated canned corn - there was a corn that was “grown in a specific field of Idaho” that was “the best in the world.” Only problem: there wasn’t much of it. TJ’s bought it up and “when that was gone, that was it, until next year” (126).

Heisengberg’s uncertain blend of coffee - when coffee roasters process beans, a few fall off the conveyor belts. “Periodically, they would sweep these up, roast them, and sell them to us for very little money” (130). Every batch was different, thus the fun name, and customers loved the price.

Traditional supermarkets would never touch either of these products. They would not be in quantities necessary for mass distribution and they’d be hard to explain (TJ’s has a newsletter called the Fearless Flyer, where they educate customers on the deals they find).

When it comes to discontinuity, the travel industry does pretty well. We’re used to rare experiences and perishable inventory. There are a range of revenue management strategies to get rid of strange or poorly selling inventory, from flash sales to reducing the cost of loyalty point redemptions. Media like TravelZoo specialize in limited-time, discontinuous deals for hotels, cruises, and tours and email newsletters like Going direct attention to cheap airfares.

Still, I think there’s opportunity for more. For example, retailers could curate and package deals that align with an audience. Antarctica Travels does this for Antarctica expedition cruises, but I could imagine it for other niches (luxury safaris, guided adventure travel, high-end beach vacations, long-duration cruises).

Store Brands

When Coulombe settled on the final concept for Trader Joe’s, he committed the company to store brands. Here’s how he described the strategy:

Drop all ordinary branded products like Best Foods, Folgers, or Weber’s Bread. I felt that a dichotomy was developing between “groceries” and “food.” By “groceries” I mean the highly advertised, highly packaged, “value added” products being emphasized by supermarkets, the kinds that brought slotting allowances and co-op advertising allowances. By embracing these “plastic” products, I felt the supermarkets were abandoning “food” and the product knowledge required to buy and sell it. (97)

Store brands are not an innovation unique to Trader Joe’s, but I think Coulombe’s rationale is relevant to travel retailing for one reason: distribution costs.

Hotels are rumored to pay Expedia up to 30% to be listed prominently on the site (the average is likely 20%, according to unsourced articles). Beyond commission, hotels have their own marketing budgets, sales forces, and loyalty programs (those points aren’t free). That means a significant proportion of the price a consumer pays covers distribution costs - basically the money the hotel paid to find that consumer!

There are reasons for all of this (how would consumers find hotels at all?), but I also think these distribution costs can be compared to the slotting allowances, co-op advertising, and coupons that branded food companies pay supermarkets. The travel industry is used to things working this way. When you buy Best Foods mayonnaise at a supermarket, you’re partly paying for the slotting allowance - for that product to be on a shelf at your eye level.

Coulombe took a simple approach:

Trader Joe’s buying objective was to get just one, dead-net price, delivered to our distribution centers. (190)

Offering white-labeled (unbranded) products and negotiating low “dead-net” prices is common in travel. Again, I’ll point to package tour operators in Europe.

That said, I still wonder if there’s more opportunity here, especially when combined with all the other elements I’ve discussed here and when aimed at an “overeducated” consumer.

Intensive Buying at a “Buyer-Oriented” Company

Coulombe does not see TJ’s as a customer-oriented company. If you’re used to business pablum, you may be scratching your head.

When Coulombe finally settled on the winning formula for Trader Joe’s (a decade after founding), they did something really different:

We fundamentally changed the point of view of the business from customer-oriented to buyer-oriented. I put our buyers in charge of the company.

[…]

We violated every received-wisdom of retailing except one: we delivered great value, which is where most retailers fail. (96)

What exactly does a “buyer-oriented” company do? It puts the buyer’s taste, savvy, and negotiating skills at the center in a process that Coulombe calls “Intensive Buying.” Buyers become knowledgeable about their product categories (since TJ’s has so few products), they’re constantly on the hunt for deals, and they also change product specifications to improve quality, value, and/or uniqueness.

Here’s an example:

Supermarkets sell fish “from their meat departments, usually in thawed (so-called fresh) form […]. In their frozen food departments, you only see branded seafoods: seafoods that have been value added, like breaded fish sticks, stuffed crab, etc.” (110)

Trader Joe’s saw an opportunity. Most “fresh” fish was frozen anyway. Why not cut and package fish in a factory and then sell it frozen? TJ’s would minimize processing and labor and could pass the savings on to consumers. They started selling plain frozen fish without any “value added” modifications and became one of the major retailers of fish within three years. “To achieve this, Trader Joe’s had to learn about seafoods and often interfere in the packaging, transportation, etc of the products. But we became the No. 1 retailer of Black Tiger Shrimp in the country this way” (110).

That’s intensive buying. Coulombe’s full definition:

Intensive Buying stops short of actually manufacturing the product and may even stop short of physically handling the product at any point before it reaches the distribution center. Intensive Buying is a program of vertical interference and supervisions, but not vertical integration. (112)

And an addendum:

Intensive buying assumes no hay precios fijados (there are no fixed prices). (110)

The book goes into detail on tactics, but what stood out for me was that intensive buying requires good vendor relationships. It’s not about squeezing a seller for every last penny.

The buyers would get ideas by working with their vendors and they’d collaborate to change products and increase value. Some tactics TJ’s used to get good prices included paying cash on receipt (and calculating a discount accordingly), paying in local currency (then hedging themselves, not accepting a vendor’s inflated risk markup), and making quick buying decisions, including meeting on short notice. “Desperate vendors knew they would not be strung out by a constipated buying pressure. They might not like they offer they got, but by God they go an offer” (103).

When we compare to travel, large-scale OTAs and activity aggregators aren’t doing this at all. They rely on their size to negotiate discounts but do little else.

That said, many travel companies work with their vendors to customize offerings for their customers. The team at my company certainly does. But I suspect this is done most at the high-end companies like mine, and the focus is more on increasing quality and uniqueness, not necessarily on find high-quality bargains.

What do you think? Is there room for a travel retailer that’s inspired by Trader Joe’s?

In the last few years, there have been controversies at Trader Joe’s related to product naming (is “Trader Ming’s” racist?), copying and undercutting ideas from food entrepreneurs, and union busting. I’m not going to cover any of those here since I’m focused on Coulombe’s development of the original concept in the 1970s and 1980s (which is mostly intact today).

The difference in SKU count is more extreme when you compare TJ’s to a Walmart, which carries ~140,000 SKUs or Amazon.com, which carries hundreds of millions.