#14: Five ideas from the airline business

Aviation is the most brutally competitive part of the travel industry. These are five of my favorite airline business concepts.

The business of transporting people from city to city by air unites the massive with the microscopic. At the beginning of each day 4,500 giant aluminum vessels start their engines and fling themselves into the air over the United States. With paying passengers aboard, they fly at nearly the speed of sound to their destinations, disgorge themselves, fill up again, and fly on. They repeat this process through the day a total of 20,000 times [...]

Repetitiveness on this scale means that success and doom occur in the margins of the airline business: bad business decisions have a way of becoming catastrophic; good calls look in retrospect like acts of genius. It costs anywhere from seven to fourteen cents to fly one passenger a mile, and with nearly a half-billion passengers a year flying nearly a half-trillion miles, the pennies have a way of disappearing quickly.

-Petzinger Jr., Thomas. Hard Landing: The Epic Contest for Power and Profits That Plunged the Airlines into Chaos

Here are five business concepts that stick with me from this hyper competitive industry:

Hub-and-Spoke vs Point-to-Point networks

Trip Cost vs Unit Cost

High Opex, Low Capex

Out and back flying

Outrage marketing

Idea 1: Hub-and-Spoke vs Point-to-Point networks

There are two ways to design an airline route network. You either run a point-to-point airline (exemplified by Southwest) or a hub-and-spoke airline (like Delta).

Point-to-point airlines mainly serve direct traffic between cities. The game is maximizing earnings with a plane over the course of the day, which usually correlates to maximizing time in the air (“planes on the ground don’t make money”). Airlines like Southwest hop from one route to the next to maximize utilization of their planes.

With a hub-and-spoke model, the game is maximizing connectivity, which in turn maximizes revenue potential. Every city added gives an exponential number of city pairs. This is most obvious when looking at super-connectors like Turkish Airlines (Porto to Entebbe in one stop!). There are inefficiencies with a hub-and-spoke model:

Hubs are only busy at peak times of day

Planes sit on the ground, waiting to fly at times that maximize connections

Individual flights may not be profitable on their own, but they’re needed to connect passengers to journeys that are profitable overall.

If you’re interested in more, United’s Patrick Quayle was interviewed by the WSJ.

Both models work. A direct flight is convenient, and hubs connect passengers to the world.

Idea 2: Trip Cost vs Unit Cost

This is a story of questioning the metric that everybody focuses on. In the airline industry, people obsess over minimizing costs and analysts judge airlines by their CASM (Cost per Available Seat Mile). This is a unit cost.

About 18 years ago, David Neeleman was ousted from JetBlue, the airline he founded a decade earlier. Within a year, he founded an airline in Brazil called Azul (get it?). Azul focuses on cities with little or no air service, and they operated much smaller planes to do it.

Neeleman popularized a focus on trip cost rather than unit cost (though this is not a new idea. I’ll get to that in a second). What’s the difference?

Trip cost is the total cost of operating one flight on a plane. It may cost $8,500 to fly a 737 (seats 175) for a one-hour flight and it may cost $6,500 to operate a smaller regional jet (seating 88). on the same flight. The larger 737

Unit cost is the cost per seat, regardless of whether it’s filled or empty. Bigger planes have more seats, so even though their trip costs are higher, the cost per seat is lower since they’re spreading those costs over more people. Assuming the seats are full, of course…

Here’s Neeleman’s insight:

Of the 22 markets we fly, in 16 we’re the only nonstop. And the others, with one exception, we’re the market leader. The interesting thing about the Embraer 195 is that our trip cost is about 35 to 40% less than those guys [legacy airlines flying larger planes - Jess]. So that means you can actually be making 15% to 20% on a market and they could be losing 20%. We have higher RASM [measure of unit revenue] than they do. Even though our average fares are less. For example, we had in May an average fare that was 30 Reais [about US$17] less than they had, but our RASM was 20% higher because we had an 85% load factor and they had a 58% load factor. - David Neelman speaking to Cranky Flier in 2010

If your eyes got crossed reading that (and you still care), don’t worry. Here’s a chart that illustrates what he means…

While a larger 737 has lower unit costs, that’s actually not advantageous on lower traffic routes. If there are only 70 people who want to fly between two cities, a smaller plane with higher unit costs (and lower trip cost) is just fine. In high traffic markets, of course, the advantage is reversed. You want bigger planes with lower unit costs.1

[An aside: My very smart friend™ Rohit points out this example is simplistic. In reality, the Scenario 1 737 would have more customers and a lower average price, though the end result would be similar. In the future, I’d love to write a post exploring revenue management more deeply. Thanks Rohit!]

The smaller-plane playbook is associated with Azul and Neeleman - he’s trying it again with Breeze - but it’s just a version of a general point. The reason the A380 failed was that it minimized unit costs (or tried to) when most international flights don’t have that much demand. Smaller planes like the 787 allowed airlines to serve the right number of customers, even if unit costs are a bit higher. You want a plane just big enough to fly the high revenue folks and small enough that you don’t have to discount to fill the plane. Very few networks justify a plane as big as the A380.

The lesson? We often focus on one or two metrics to judge a business. Sometimes there’s opportunity in saying - what if we did the opposite?

The next idea is my favorite one of those inversions.

Idea 3: High Opex, Low Capex

Conventional wisdom is airlines are high-fixed-cost businesses. Planes are expensive, so you should fly them as much as possible. But what if that wasn’t true?

While most airlines maximize flight hours, one does the opposite.

Allegiant Air prides themselves on operating old planes. Why? They’re cheap. But, like the used car you bought for $5,000, the maintenance and gas are more expensive than a new car. Allegiant flies 20-year-old gas guzzlers. Other airlines fly new Priuses.

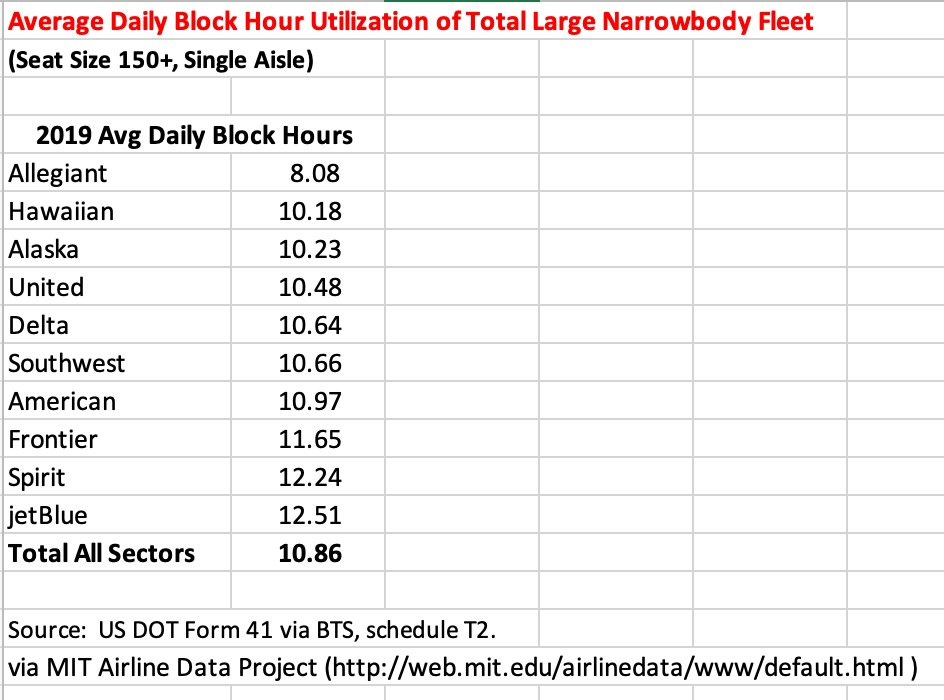

Shifting to a higher proportion of variable costs means Allegiant can operate fewer hours a day and cover their low fixed cost base. Instead of flying as much as possible to pay a lease/loan, they only fly when the prices are high. In 2019, Allegiant flew 2 hours less than the industry average and 4 hours less than Spirit and Frontier. Allegiant’s low capex/high opex model contrasts with the high capex/low opex model of low-fare airlines like Spirit. When you have expensive, efficient planes, you need to maximize utilization to cover the high lease/loan costs.

Airlines with this model can think like a variable cost business - they only “produce” capacity when there’s demand. Planes sit on the ground until they're needed for a profitable flight at a different time of year or a different day of week. Sun Country, which operates using a similar model, flies 60% of their peak capacity in September and less than 50% of their peak capacity on Tuesdays.

The lesson? There can be opportunity in flipping standard assumptions around, especially in capital-intensive businesses with variable demand. Allegiant doesn’t compete direction with traditional airlines, but they’ve created a very profitable niche that’s only possible with their low capex/high opex model.

Idea 4: Out and Back Flying

You either run planes out of your bases or you hop around, flying between whatever cities have the most demand.

All airlines have operational bases. Crew live nearby (or are responsible for getting themselves there), there’s some maintenance infrastructure, and usually there are spare planes. For hub-and-spoke airlines, hub are bases.

Things get more interesting for point-to-point operations. If an airline wants to serve two cities where it doesn’t have a base, it needs to incorporate that city pair into its schedule. If you have a base in Dallas and want to fly between St. Louis and New Orleans, then you might organize a plane and crew to fly Dallas→St. Louis→New Orleans→Dallas, starting and ending a day at the base.

Problem solved… But what if there’s a massive delay in St. Louis?

Remember the Southwest Airlines meltdown in December 2022? One of the causes was Southwest’s network design:

While Southwest does have major connecting airports, much of its schedule involves planes and crews crisscrossing the country – a network that aviation watchers say is more vulnerable than legacy carriers’ hub-and-spoke model [sic] that can contain a disruption to particular geographic regions.

- “Insiders at Southwest reveal how the airline’s service imploded,” CNN

That quote is a bit misleading. While hubs are bases, the real purpose of a hub is connecting passengers. Point-to-point airlines, which mainly serve passengers between direct city pairs, can also offer “out and back” flying.

An out-and-back network has three advantages:

Crew sleep at home (usually), saving money on hotels and meals.

Delays are isolated, leading to more resiliency. Problems don’t cascade.

Unprofitable flights can be cancelled without knock-on effects. Hub-and-spoke airlines can't cancel individual flights, since passengers connect to other flights. Point-to-point airlines like Southwest schedule their planes on a series of flights across the network, so again they can’t cancel any one of them.

In 2020, at the peak of Covid-related uncertainty, Allegiant took advantage of their out-and-back model:

We are seeing the benefits of our model. Compared to operating a hub and spoke or a point-to-point schedule, our basing approach with aircraft and crews together is easier to manage. The out and back nature of our flying has allowed us to offer most of our schedule for sale and within 10 to 14 davs before the scheduled flight cancel ones that did not make sense. Our economic justification for flying flights was based on the flight contributing positively to our cash balances, namely covering the direct expenses of fuel and airport costs.

Source: 2020 Allegiant Investor report

There are three downsides to the out-and-back model:

Less network flexibility, since all routes start/end at a base airport. It’s harder to chase high revenue if an airline hews closely to the out-and-back model.

Upfront investment is higher. New bases require local hiring. It’s harder to test new non-base routes (airlines can choose to tolerate some non-base flying for the sake of testing).

It requires scale. You need to operate enough flights to cover the cost and infrastructure of a base.

Out-and-back flying is more common in Europe. Ryanair, for example, only flies to or from its base airports. In the US, the FAA requires base airports to have more spare crew, which means that bases need more scale in order to make sense.

The lesson? Limitations can create a structural cost advantages and resiliency.

Idea 5: Outrage marketing for the cheapest option

I’ll end on a fun one. In 2022, Ryanair’s social media account blew up for their mean (and funny) responses to customers.

This tone is not new. CEO Michael O’Leary is notorious for making controversial pronouncements — on a short flight, why not charge money for bathrooms so fewer people use them? Check out this headline from 2009.

Ryanair’s PR strategy seems crazy until you realize two things:

They rely heavily on direct bookings (not OTAs like Kayak or Expedia). Ryanair needs to remain top of mind, which means all publicity is good publicity.

There’s one theme across social media and absurd ideas from O’Leary: Ryanair is the cheapest option (and they’re fighting to make it even cheaper).

Outrage marketing like this works particularly well when you’re the cheapest option.

You might ask: Why not lower price in scenario 1 to fill the 737? Stimulating demand works in some cases, but in others you end up eroding the revenue you already have. Those first 70 passengers were willing to pay $110. But now that you’re selling tickets for $50, all the passengers will want tickets that cheap. There are ways to segment demand, but it only works in some situations.

I've always appreciated RyanAir's approach, it's the most earnest of the airlines. Many legacy carriers tip toe around the issue but RyanAir just dives right in. They fill their marketing with allusions to a refined product. Airlines for the most part are a utility and cost is the primary incentive to demand followed closely by convenience. No airline save a few major Asian and Mid East carriers truly differentiate on service or quality and that's mostly limited to long haul flying. But domestic airlines in particular would do well to maybe be truly honest about their brand role and why flyers actually choose their product. Cost and convenience dictate. Many airlines have tried to differentiate but almost all seem to regress to the mean eg Alaskan.

And don't get me started on AA's past 12 months of commercial decision making...