#17: Niche cruise products: Why they work and how they might grow

River and coastal cruising defy the industry's standard playbook. Why don't established players enter these niches? And what's their future?

There’s a playbook - developed in the 70s, perfected in the 90s - for operating a successful cruise line:

Foreign-flags from countries like the Bahamas minimize taxes and allow companies to hire crew from countries with lower wages.

Economies of scale lower per-bed costs. This is partly why ship keep getting bigger.

Go-anywhere ships - most cruise ships can sail worldwide. Executives remind investors that ships are movable assets. A recent example: Economic weakness in the EU and China have led Royal and Carnival to shift capacity to North America.

Operate year-round - why wouldn’t you? Oceangoing ships are expensive to build, and they can’t be “turned off.” Out-of-service ships still need a (smaller) crew and regular maintenance. During the pandemic, Carnival estimated the cost of a “hot layup” at $2-3 million per ship per month. That doesn’t include the shutdown/startup costs of flying the non-essential crew in and out. Even with lower off-season revenue, it’s usually more profitable (or less loss-making) to keep a ship in service.

That’s the strategy followed by the big four - Carnival, Royal Caribbean, NCL, and MSC - and it’s been enormously successful.

But strict adherence to this approach leaves opportunities for others. While the big players stick to what works, new entrants - like Viking - create surprisingly large businesses in the niches. And eventually, they can grow into “real” ocean cruising competitors.

Here, I’ll look at two of those niches: river and coastal cruising. How do they deviate from the cruise industry playbook and why do they still work as businesses? Then, I’ll discuss why the big cruise companies don’t go after these niches and the potential opportunities for new entrants.

The River Business

River vessels diverge from the cruise industry playbook in most ways:

Subject to local regulations & higher labor costs. In Europe, for example, staff on river vessels need permission to work in the EU and are paid European wages and benefits.

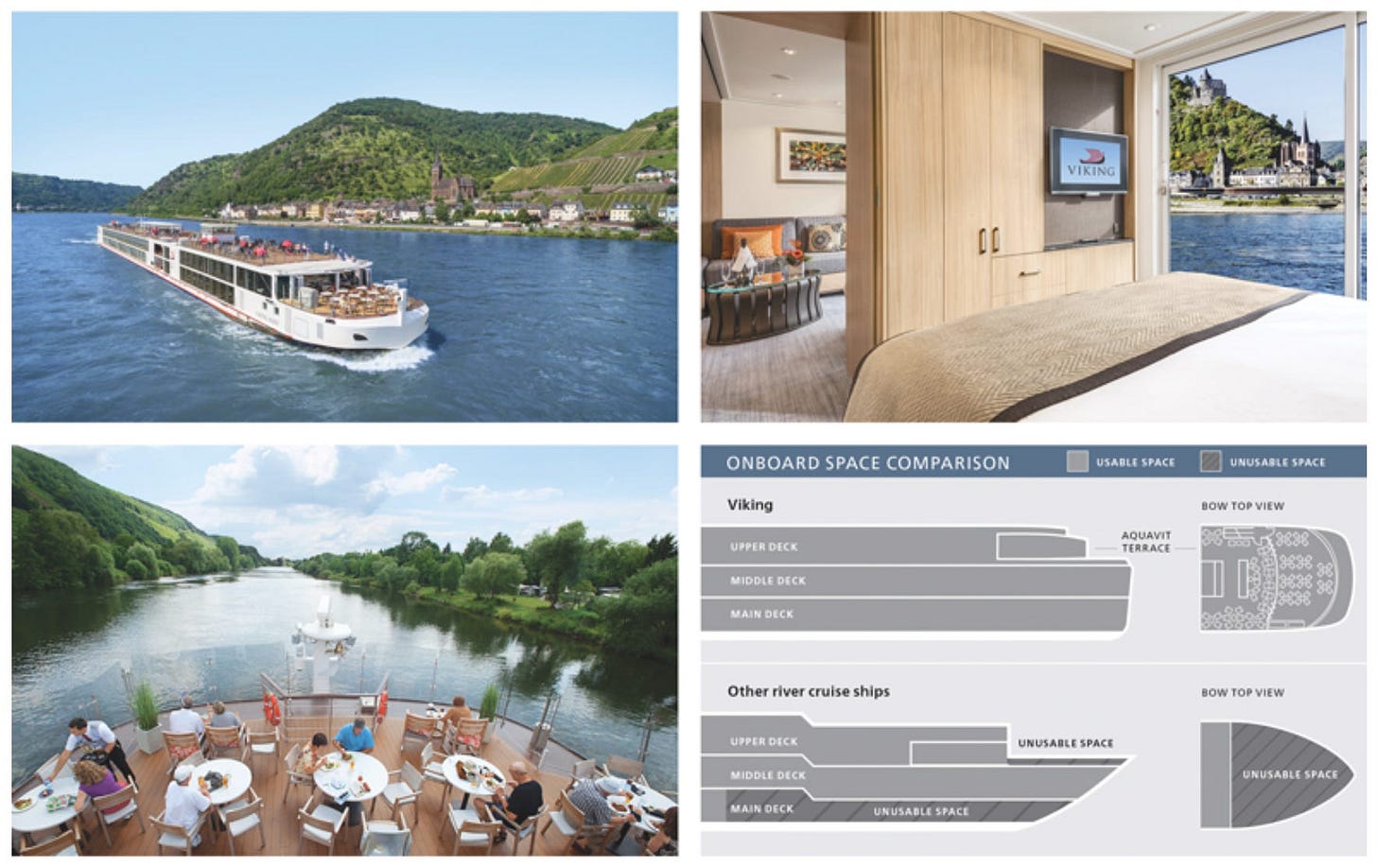

Smaller scale, due to the size limits of the rivers on which they operate. Most European river vessels carry under 200 passengers and have maximized designs. There’s not room to push economies of scale.

Designed for specific operating areas. River vessels are designed to operate under the constraints of a given river (and comply with local regulations). While European river vessels can move throughout the Rhine-Danube network, extending from the Netherlands to Romania, they cannot be moved to smaller rivers like Portugal’s Duoro or France’s Seine.

Operate 8-9 months of the year in Europe, the largest river cruise operating area. In some other places, they operate year-round.

That may sound negative, but there are benefits to river vessels vs oceangoing ships which negate these disadvantages. I’ll enumerate them here, using Viking Cruises as an example since they operate both river and ocean ships.

Freshwater operations mean maintenance costs are lower and the expected life of the vessels is longer. Viking estimates their river vessels have a useful life of 40-50 years compared to ~30 years for ocean ships, which operate in corrosive saltwater. Freshwater operation also makes it easier to lay up a vessel for a few months with minimal maintenance.

A simpler product focused on the destination. River boats are floating hotels, not resorts. They’re in port almost every day, and passengers are focused on touring. Compared to oceangoing ships, they need fewer services and public areas. That has some knock-on benefits 👇

Fewer crew members per passenger. A Viking longship has 3.6 guests per crew member vs 2 guests per crew member on their Ocean ships (53 crew members for 190 guests on river, 465 crew for 930 guests on Ocean). Salaries for European crew members on the river vessels are surely higher, but the overall labor budget per passenger is likely similar on river vessels because of the higher ratio.

Less space per passenger. A Viking river boat has half the space per passenger of their ocean ship (26 gross tons per passenger vs 51 on an ocean ship). Why? River boats have smaller cabins and fewer public areas. They also need less back-of-house space since there are fewer crew and they can restock more frequently. No need to store weeks of food and equipment for a long cruise. Cramming in more guests results in lower building costs on a per-bed basis. It costs Viking half as much to build a river vessel as an oceangoing vessel (~$230K vs $447K).

Coastal Cruising

There’s more product variation in this category. A couple examples:

American Cruise Lines operates US-flagged river and coastal boats on domestic American itineraries. They’re on a growth tear, with 7 vessels on order.

Variety Cruises operates boats with fewer than 72 guests in Europe, Tahiti, the Seychelles, and West Africa.

Guntu is a boutique luxury hotel that floats around Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. One of the most beautiful vessels in the world.

Croatia Cruises operates yacht-style boats with fewer than 40 passengers in - you guessed it - Croatia.

Lindblad operates four US-flagged coastal vessels on expedition cruises in Alaska, the US West Coast, Baja, and Latin America.

Coastal vessels are subject to some limitations compared to their oceangoing peers:

Local regulations and labor laws. For example, US coastal vessels employ American crew members 🤑.

They’re smaller, though size constraints are driven by the desirability of access to small, differentiated destinations. Limitations are not as rigid as river vessels.

Many operate seasonally, similar to river cruise lines.

Only operate in sheltered waters or coastal areas, where they can quickly hide if the weather turns. Unlike river vessels though, they can move between operating regions. Longer moves might require a relocation service (similar to yachts that move on larger ships).

Again, there are benefits that come from accepting these limitations. Here are a couple advantages I’ve seen, though they don’t apply to every coastal vessel:

A simpler product focused on the destination. Because these boats are in port every day, guests don’t need multiple restaurants and big cabins. That can lead to the same crewing and space advantages as river vessels. As a result, coastal vessels have lower building cost per passenger than an equivalent oceangoing ship.

Itineraries that stop in port every night - this is an extension of the “simpler product” point. Some companies offer yacht-style itineraries that stop in a town every night. Guests get off to explore town and eat dinner, a good customer experience. But this choice also allows a company to hire fewer navigational staff (no overnight sailing) and fewer cooks (serving 2 meals/day).

Access destinations that foreign-flag ships can’t. This is due to their size and shallow draft, but it's also due to their status as domestic vessels. Foreign vessels are required to dock at facilities with a secure setup under something called the ISPS Code. Not only do they need security guards and fences to control who accesses the port, they also need to get that setup registered with local authorities. This is an international regulation, so it applies everywhere. My point? Domestic vessels don’t need ISPS facilities. If a boat fits at a dock or its smaller tenders can get there, then it’s fine. That opens up destinations and docking locations that are not accessible to most cruise ships. A small foreign-flag ship might physically fit at these locations, but they still wouldn’t be allowed to use them (or would require an expensive temporary security set up).

Lower port and pilotage costs. In some areas, port fees (for docking, security guards, linesmen etc) and pilotage fees (for mandatory local pilots) are a significant portion of operating costs. Big, foreign-flagged ships easily spread these costs over thousands of passengers but for smaller high-end operators, they’re a major consideration. Alaska, for example, is an extremely expensive place for small, foreign-flagged cruise lines. Domestic vessels have advantages that significantly reduce both costs. Port fees can be reduced by docking at non-ISPS facilities. Domestic operators can cut deals with anybody who has a dock that fits. Pilotage costs are saved if the ships navigators qualify for pilotage exemptions. If they’re familiar with local waters and sailing a domestic vessel, they don’t need to bring on a local pilot, another huge saving.

Why don’t the established players participate in these niches?

Yes, these niches defy the standard industry playbook, but they clearly can be profitable. Why don’t Carnival, NCL, or Royal have a river cruise division?

First, these niches are inherently premium and high-priced. They’ll never beat foreign-flagged 4,000 pax ships on cost due to their small size and high labor costs. River and coastal cruising require customers who pay a premium for access to smaller destinations.

In the US, prices on American or Lindblad are $700 to $1,000/day.

In Europe, companies like Variety and Viking sell in the $300-500/day range.

High-growth from Viking and American Cruise Lines suggests the demand for these premium products is larger than we think, but it will always remain a lower volume/higher value segment.

The high prices and small size of river and coastal vessels make them seem like toys to the “big guys.” In June, after the enthusiasm of Viking’s IPO, Carnival’s CEO was asked about the river business:

We’ve looked at river cruising in the past, and I wouldn’t say we’ll never look at it again.

It’s just — it’s a niche, and it’s rather small. And for something like us to move the needle, it’d have to be pretty grand. And as you’ve heard me say before, I think if we focus on our brands and we focus on doing all the things that we do in the normal course better, we’ll make much more of an impact on this business.

Josh Weinstein, Carnival Corp CEO in June 2024 (via Cruise Industry News)

Focus is the right move for Carnival. They’d have to flood the river market with capacity in order meaningfully increase their own revenue - Viking’s entire river division equates to 10% of Carnival Corp’s revenue. Starting a river brand would require more effort and risk than building demand for existing ocean brands.

But the big companies’ focus leaves opportunity for others. It’s a weak version of Hamilton Helmer’s counter-positioning:

Counter-Positioning: A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

from Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (source)

River cruising wouldn’t damage the established ocean business (thus, "weak” counter-positioning), but it always seemed like a distraction. And that allowed a new competitor to emerge.

When river cruising boomed in the 2010s, none of the big cruise companies entered the market. It seemed too small. Unchallenged, upstarts like Viking and AMA built multi-destination river brands with products in Europe, Egypt, SE Asia, and Africa. Viking eventually used their river customer-base to launch an ocean division, allowing them to maintain aggressive growth into the future. In 2023, Viking’s revenue was 55% of NCLs, the smallest of the traditional cruise companies, and 20% of Carnival’s. Viking became the smallest of the “big guys,” and they’re growing faster, too.

(An aside: It’s no coincidence that the classic “premium,” destination-oriented brands at Carnival - HAL and Princess - have barely grown while Viking has boomed. By allowing Viking to build a loyal customer-base with a product better targeted at premium customers, Carnival ceded growth in that segment without realizing it.)

Two things can be true at the same time:

The best way to grow an already-large cruise line is with (big) ocean ships. A disproportionate share of Viking’s future growth will come from the ocean business, proving Weinstein’s point.

Niche cruising can be a great (smaller) businesses, and it’s unlikely to be challenged by the established players. That makes it a great way to start a new brand without competing head-on with the incumbents.

Is there more opportunity in the niches?

River cruising is, to some extent, played out. The existing brands will continue to grow, but there’s unlikely to be a major new entrant.

But what about coastal cruising? Is there an opportunity for a coastal cruising mega-brand? Similar to river, which has multi-destination brands like Viking and AMA, coastal cruising could consolidate and grow with scaled distribution and product consistency. It certainly seems like an opportunity for a rollup, a brand extension (Viking?), or an entirely new brand.

One last point: I suspect coastal and river vessels will be the first cruise ships to decarbonize. A few reasons:

The vessels are smaller, meaning less aggregate energy is needed. Destinations won’t need to build a power plant to refuel a ship.

River and coastal vessels often travel regular routes, meaning it would be easier to justify investment in fueling and charging infrastructure.

They travel short distances and are in port almost every day, so they wouldn’t need much range. Ocean-going ships, by contrast, need the autonomy to cross the Atlantic.

Norway already has battery-powered ferries in service. Electric or hybrid cruises might be feasible within a decade.

Communities are also growing increasingly skeptical of large, foreign cruise ships. From Mallorca to Bar Harbor, overtourism protests and citizen ballot measures may restrict visits from large ship. Coastal and river vessels - that employ locals, purchase local food, visit regularly, and carry fewer passengers - are likely to be seen favorably. Especially if they decarbonize first.

Sustainability can be a tailwind for these niche cruise products, and it may give access to places that are closed to traditional ships.

Thanks for reading!

🔗 Related Links 🔗

⛵ Quirky Cruise is a review website for niche cruises, including small coastal vessels. You’ll be amazed by the variety of small-ship cruise experiences that are out there, like these 9 options in Scotland.

📝 Whitepaper on Future of the Fjords, a zero-emission tourist vessel in Norway. The boat goes on 2-3 hour sightseeing cruises and charges for 20 minutes between cruises. The paper discusses the vessel’s design and how to build fast-charge infrastructure in a remote place (hint: floating docks with batteries inside).

🔋 The Rise of Batteries in 6 Charts - context for when electrification might come for ships and planes. Long-distance transport is the one of the hardest areas to electrify. It turns out oil products are really energy-dense.